Welcome to the

20

21

State of the Sector Report.

PeopleBench would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the country on which we are privileged to live and work.

In the spirit of reconciliation, we recognise that sovereignty of these lands was never ceded. We pay our respect to elders past, present, and emerging and extend this respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

State of the Sector

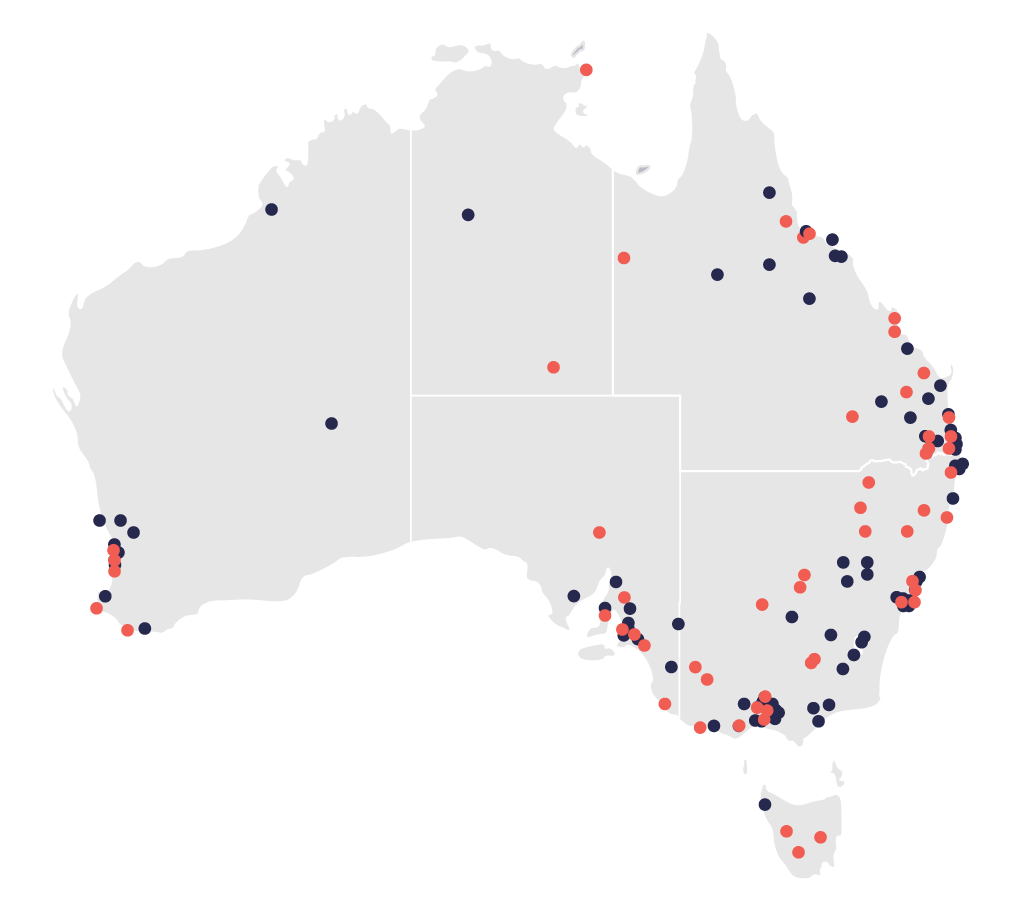

This report reflects the responses of

Across Australia.

While this represents a small slice of the national K/P–12 school landscape—there are 9,621 schools reflected in the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority’s (ACARA) data for 2020—it is reasonably representative of the population in terms of school sector (the split of Government, Catholic, and Independent schools), school type (Primary, Secondary, and Combined Years), school size, and geography.

State of the Sector

Introduction

Welcome to the second PeopleBench State of the Sector Report. This report summarises the results of a survey that was conducted in March, 2021, and was designed to gather the perspectives of Australian educators about the challenges and opportunities they face in the school workforce.

Section one:

Sector

Sentiment

Sentiment /ˈsɛntɪm(ə)nt/ noun a view or opinion that is held or expressed.

It’s challenging to be an educator right now. Educators routinely teach and lead in circumstances that are volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous at the best of times—not to mention the impacts of a global pandemic. In this section, explore the sector’s sentiment through the lens of educators and education leaders as they reflect about their own role in the education workforce today, and the school workforce overall, and as they imagine the education workforce three years from now.

Section one:

In one word, how do you feel about your role in the school workforce today?

To get a quick gauge of educator sentiment, we asked respondents to sum up how they felt about their current role in one word.

A total of 312 people responded to this question. The words they chose painted a vivid picture of the challenges facing educators after a year of disruption and uncertainty due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the words chosen were many and varied (and included optimistic words such as Positive and Excited), the most commonly-used words centred around themes of exhaustion (Exhausted, Exhausting, Tired) and busyness/workload (Busy, Overworked).

The overall tone of the sentiment expressed here should raise alarm bells for the future of the teaching profession and school workforces. Negative perceptions are likely to negatively impact attraction and retention of current and future teachers. Research has consistently found that where teachers feel valued and are satisfied in their jobs they are more likely to remain in the profession (Schleicher, 2018).

Section one:

In one word, how do you feel about your school’s workforce overall today?

We also asked respondents to sum up how they felt about their school’s workforce as a whole in one word.

A total of 317 people responded to this question. The words they chose reflected similar themes and patterns to the previous question. The most commonly used words centred around themes of workload (Overworked, Overwhelmed, Busy) and exhaustion (Tired, Exhausted).

Despite this, a sizeable minority of respondents chose optimistic words such as Supportive, Committed, and Proud.

Section one:

Reflections on the school workforce today

To explore sentiment in more detail, we asked respondents to rate their agreement (using a five-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree) with three statements about the school workforce today.

Again, responses to these questions revealed stark differences by role type, with Principals more likely to report feeling excited, confident, and well-prepared than respondents in other roles.

Teachers and Middle Leaders typically reported feeling least excited, confident, and well-prepared; responses from Other Senior Leaders and HR/Business Support staff typically fell in-between.

The less positive sentiment expressed by Middle Leaders may reflect that these roles often require incumbents to juggle a teaching load with their first managerial position and are subjected to pressure from both above and below, and frequently feel tension between their department and the whole-of-school direction (Harris & Jones, 2017).

When I think about my school’s workforce today, I feel excited.

Middle Leaders

Teachers

Other Senior Leaders

HR & Business Support

Principals

When I think about my school’s workforce today, I feel confident that we can execute our school’s vision.

Middle Leaders

Teachers

Other Senior Leaders

HR & Business Support

Principals

Principal confidence seems to have remained strong,

in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the 2019 State of the Sector, 93% of

Principals reported feeling confident that they could execute on their school’s vision.

When I think about my school’s workforce today, I feel well-prepared to deal with the challenges that may arise.

Middle Leaders

Teachers

Other Senior Leaders

HR & Business Support

Principals

Section one:

Key Takeaways: Sector Sentiment

-

Typically, the more senior a respondent’s role, the more optimistic their outlook on the school workforce. Principals were more likely to use positive than negative language when describing the school workforce, and were more likely than other respondents to report feeling more excited, confident, and well-prepared to manage workforce challenges. Principals’ optimism seems to have held up despite the challenges of a COVID-disrupted year—the sentiments reported in our 2019 State of the Sector report (which included only Principals and no other roles) were comparable to this year’s survey.

-

Teachers and Middle Leaders tended to use more negative language when describing both their role and the school workforce overall, and were least likely to report feeling excited, well-prepared, or confident when thinking about the school workforce now and in the future.

-

Generally, Primary school respondents were most likely to take an optimistic outlook on the school workforce both today and in three years’ time, followed by Combined Years school respondents. Secondary school respondents were least likely to report an optimistic outlook.

-

While Catholic and Independent school leaders were similarly optimistic about the school workforce today, Independent school leaders were more likely—and Catholic school leaders less likely—to be optimistic when thinking about the school workforce in three years’ time.

-

While not an assessment of wellbeing or mental health, our results suggest that many teachers—especially those in the public sector—could use additional support to deal with the demands of their roles today (particularly regarding workload and work intensification). Results also speak to a need to redesign roles in the school to allow for sufficient resources (e.g., autonomy) to buffer against the risk of burnout.

Section one:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Recognise, reward and continue to support school Principals to maintain their resilience and share their perspectives and learnings with staff across the sector

2.

Engage Middle Leaders and Teachers in the process of designing the jobs of the future, reflecting changing service delivery models (e.g., the rise of online learning and hybrid delivery), work intensification, and shifting skill requirements

3.

Explore ways to improve individual autonomy and access to support (e.g., professional development, coaching, mentoring) for Teachers and Middle Leaders

4.

Identify opportunities to improve person-job fit via appropriate professional development and career planning processes for all roles

5.

Manage the potential negative effects of sub-optimal school culture/climate by investing in building leadership capability, building psychological safety, and conducting proactive and systematic performance planning and development processes

Section two:

Strategic

Priorities

Across the sector, education leaders are managing complex enterprises—with all of their constituent functions, risks, and governance challenges and with varying degrees of resourcing and external support. Pull up almost any Australian school website and you’ll find reference to strategic planning, including, in particular, the school’s vision and mission and annual school improvement plan, and often the school’s strategic plan. In this section, learn more about the top strategic priorities of Principals and senior leaders across the sector.

Section two:

Key Takeaways:

Strategic Priorities

-

ID-19 pandemic has underlined the importance of both a) taking a deliberate and comprehensive approach to setting strategies to guide schools over the coming few years and b) planning for contingencies and potential scenarios that may affect the implementation of these strategies.

-

In our survey, school leaders prioritised Teaching and Learning Strategy above all else, but Workforce Strategy was generally regarded the second most important strategy for leaders over the next three years, regardless of school type or sector.

-

Leaders have an opportunity to use the disruption to convention that has been brought about by the pandemic to take stock of their current strategy and consider whether the plans and initiatives they currently have in place will allow them to achieve their schools’ goals, or whether a different, less conventional approach is needed.

Section two:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Leverage the learnings and opportunities in COVID-19 disruption to deliberately design new Service Delivery Models for the delivery of schooling, ensuring we establish baseline and impact measurements for student outcomes and employee experiences

2.

Review current strategy and planning frameworks and processes in schools and schools systems. Aim to move toward:

- An increased emphasis on Workforce Strategy as a key enabler of sustainable schooling and impact on student outcomes

- Longer planning horizons

- Deeper and broader engagement of school workforces and communities in the co-design of future school Workforce Strategy

3.

Examine school and system leadership team capability—and invest in building, buying, or boosting expertise and capacity to design and implement workforce improvement strategies over time

Section three:

Workforce

Challenges

In creating schools that are great places to learn, the education sector—in Australia and beyond—is challenged to make schools great places to work. The list of potential workforce challenges is long, with each contributing to the complexity and volatility of the education landscape: staff retention and turnover; workforce age; absenteeism; workforce resilience; attracting and recruiting staff; leadership pipelines; staff capability, training, and development; performance management; psychological and physical injury claims. This section presents the findings about the greatest perceived workforce challenges overall, by school type, and by sector.

Section three:

Key Takeaways:

Workforce Challenges

-

Across all sectors and school types, respondents’ top five workforce challenges were likely to include the Supply of suitable teachers, Attraction and recruitment of suitable staff, Teacher capability, Pipeline of future leaders and Improving staff resilience both this year and in three years’ time.

-

Compared to the challenges identified by a different sample of Principals in the State of the Sector 2019 report, school leaders this year placed lesser emphasis on Improving staff resilience, the Pipeline of future leaders, and Training staff. They placed greater emphasis on the Supply of suitable teachers and the Attraction and recruitment of new staff.

-

Subtle differences between sectors indicate a need for a nuanced leadership and policy response to address how the most pressing challenges play out differently across Australia’s diverse K/P–12 Education sector, in context.

Section three:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Ensure that workforce strategy, planning, and experience improvement processes systematically consider all stages of the hire-to-retire lifecycle in schools and school systems, using data to inform where finite effort and budgets should be spent on improvement initiatives in order to have greatest impact on student outcomes and the sustainable delivery of schooling

2.

Ensure that they are accessing international, national, state, and territory data on a full range of workforce variables to be certain that the factors they are focussed on addressing include not only the issues impacting them today, but also those that are trending to become issues in the short- and medium-term future

Section four:

Workforce

Supply

Much has been written about the teacher supply crisis in Australia and overseas. Teacher shortage forecasts for Australian states and territories are being measured in the thousands, and tens of thousands, with NSW alone predicting a shortfall of 11,000 teachers in the next decade. The teacher supply challenges facing regional, rural, and remote schools are becoming even more acute. Learn more about the sector’s perception of workforce supply challenges today and in the future in this section.

Section four:

Greatest Teacher supply challenge by school type

Participants’ single greatest workforce supply challenge for teaching roles varied predictably by school type.

In Primary schools, Middle Years (year 3–6) Teachers were most likely to provide the greatest supply challenge, while Other Teachers posed the greatest challenge in Secondary schools. The Other Teachers category often included Special Education and Design & Technology Teachers.

Combined Years school respondents’ greatest supply challenge was evenly split three ways: Maths, Physical Sciences, and Senior Secondary Teacher roles – this is consistent with much of the public discourse about acute Teacher shortages nationally.

Workforce Supply Challenges : Teachers

Number of responses by school type.

No Data Found

Section four:

Key Takeaways:

Workforce Supply

-

In Secondary schools, Maths teachers were most often identified as posing the single greatest teacher supply challenge, followed by Other teachers. In Primary schools, the most often-cited supply challenges were for Middle Years (Year 3–6) teachers, followed by Early Years teachers. In Combined Years schools, Maths, Physical Sciences, and Senior Secondary teachers were equally likely to be cited as the greatest supply challenge.

-

Across all three school types, Teaching Support roles were consistently cited as the greatest workforce supply challenge, though this was most pronounced for Primary schools. In both Secondary and Combined Years schools, Senior leader and Student support roles also featured prominently.

-

While patterns in the results were reasonably consistent across sectors, Government and Catholic school respondents’ greatest supply concerns related to Middle Years teachers (largely due to this sample comprising a majority of Primary schools) and Independent school respondents’ greatest concerns were for a range of Other teacher types not listed in the survey (e.g., Special Education; Design & Technology).

-

Across all three sectors, teaching Support roles were most likely to be cited as the greatest supply challenge among non-Teaching roles, followed by Student support roles.

Section four:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Ensure that they are accessing international, national, state, and territory data to understand Teacher supply and demand, turnover, capability, and capacity across all segments (Catholic, Independent and State) of the education sector in the development of informed workforce strategy for their schools and school systems

2.

Acknowledge that for some roles, and in some parts of the country, the supply crisis is unlikely to be resolved through branding campaigns, incentives, or intensifying traditional recruitment efforts. Instead, re-focus efforts on finding ways to deliver schooling with fewer Teachers (or fewer Teachers in the same location as their students) as part of the solution to supply problems, ensuring to measure and monitor the impact of these changes on student outcomes over time and adjust strategies accordingly

3.

Continue to advocate for—and invest in—policies and programs that enable the ongoing cultivation of a strong future teacher supply pipeline, and continue to advocate loudly and positively for the teaching profession

4.

Engage with Teachers of all backgrounds and career stages to understand their needs and career aspirations and co-design employee experiences that reflect a commitment to making schools great places to work

Section five:

The HR Function

in Schools

Human Resources (HR) in the education sector is on a path of maturation. As a separate organisational function, HR in schools is a relatively recent phenomenon with Principals historically carrying the bulk of responsibilities, relying on relatively little access to in-school specialist advice. However, this is starting to shift: HR functions are now moving from an operational basics level (payroll, industrial relations) to begin exploring organisational development, with some schools tackling workforce strategy and organisational and job redesign as enablers of new service delivery models and innovative pedagogy. In this section, discover more about the HR function in schools—the issues addressed, the functions managed, and the support provided.

Section five:

The school’s greatest HR strengths

When we asked participants to rate their school’s strength on a list of HR functions and activities on a from 0 (weakest) to 100 (strongest), scores were modest across the board, suggesting that few schools have a) established consistently strong HR practices, and/or b) effectively communicated the purpose of these activities in the school context so that staff understand their value.

The most consistent strength in the list was Supporting diversity and inclusion, which is critical to enabling schools to serve an increasingly diverse student population. This was followed by Training and developing staff, which is a relative strength in Education—with its formalised professional learning requirements.

The most poorly-ranked activity was Remaining engaged with staff alumni, reflective of the fact that there is little effort invested in maintaining alumni networks as a way to facilitate knowledge sharing and encourage quality staff to return to the school. In an environment of teacher shortages, such networks may provide a low-cost contribution to solving some staff attraction and recruitment challenges.

Supporting flexible work practices also yielded consistently low scores and is an area in which Education has lagged other industries. Addressing this gap represents an opportunity to attract a wider range of professionals into schools.

Supporting staff resilience was also rated poorly. Despite having decreased in relative priority since our 2019 survey, this remains a critical part of many schools’ response to the challenges explored in this report.

| School Type | Attracting new staff | Recruiting new staff | Inducting/on-boarding new staff | Training and developing staff | Providing performance feedback | Supporting flexible work | Managing workplace culture | Managing workplace climate | Supporting return to work | Supporting transition to retirement | Supporting diversity and inclusion | Remaining engaged with alumni | Supporting staff resilience |

| Combined Years | 68 | 66 | 65 | 61 | 54 | 45 | 67 | 64 | 60 | 55 | 62 | 44 | 54 |

| Primary | 62 | 61 | 63 | 75 | 61 | 58 | 67 | 69 | 64 | 62 | 70 | 45 | 63 |

| Secondary | 50 | 51 | 49 | 54 | 46 | 43 | 44 | 44 | 50 | 44 | 54 | 31 | 38 |

| All | 61 | 60 | 57 | 62 | 54 | 52 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 53 | 62 | 39 | 51 |

Section five:

Key Takeaways:

The HR Function in Schools

-

Regardless of school type, the HR activities most-often performed in schools were Recruitment, Employee/Industrial Relations, and Workplace Health and Safety. Workforce strategy and planning was among the least-cited functions performed at the school. It was relatively common for respondents from Primary schools to be unsure about which HR activities were performed at the school.

-

While most respondents were reasonably satisfied with the HR knowledge and amount of support available at their school, relatively few felt that these factors were Optimal, and a sizeable minority (generally between a quarter and a third) reported that they were Insufficient to meet the school’s needs.

-

While respondents identified some valuable strengths in their school’s HR function (Supporting diversity and inclusion; Training and developing staff), they also called out consistent areas for improvement across the sector: Remaining engaged with alumni; Supporting staff resilience; and Supporting flexible work.

-

Overall, results speak to the progress the HR function has made within the K/P–12 Education sector. As the function continues to grow and mature, leaders should focus on expanding the breadth of the function—emphasising strategic value-adding activities, not just the operational activities—and increasing the amount of support available to schools.

Section five:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Examine their current HR approach, considering where on a maturity continuum of transactional/operational to strategic they currently sit, and how this might need to evolve in response to current and emerging trends in the discussion about workforce strategy as it relates to schooling sustainability, impact, teacher effectiveness, risk management, and governance into the future

2.

Investigate the level of HR capability and capacity they have access to now, and consider how they may wish to build, buy, or boost this expertise in their school or system moving forward, in order to achieve their highest impact in the communities they serve

3.

Consider using the development of workforce strategy and planning processes as a vehicle to drive HR capability uplift and broader workforce engagement in building schools that are great places to work (as well as to learn)

Section six:

Professional

Development

In an environment that is changing as rapidly as education, the continuous improvement of workforce capability becomes all the more vital. Schools approach the delivery of professional development (PD) in a variety of different ways ranging from quick-fix, individually-sourced PD sessions to whole-of-school, or even system-initiated professional learning. We asked Principals and school leaders a number of questions about the vehicles offered for professional development. In this section, learn more about the sector’s perspective on professional development priorities for 2021 and beyond at an individual and school level.

Section six:

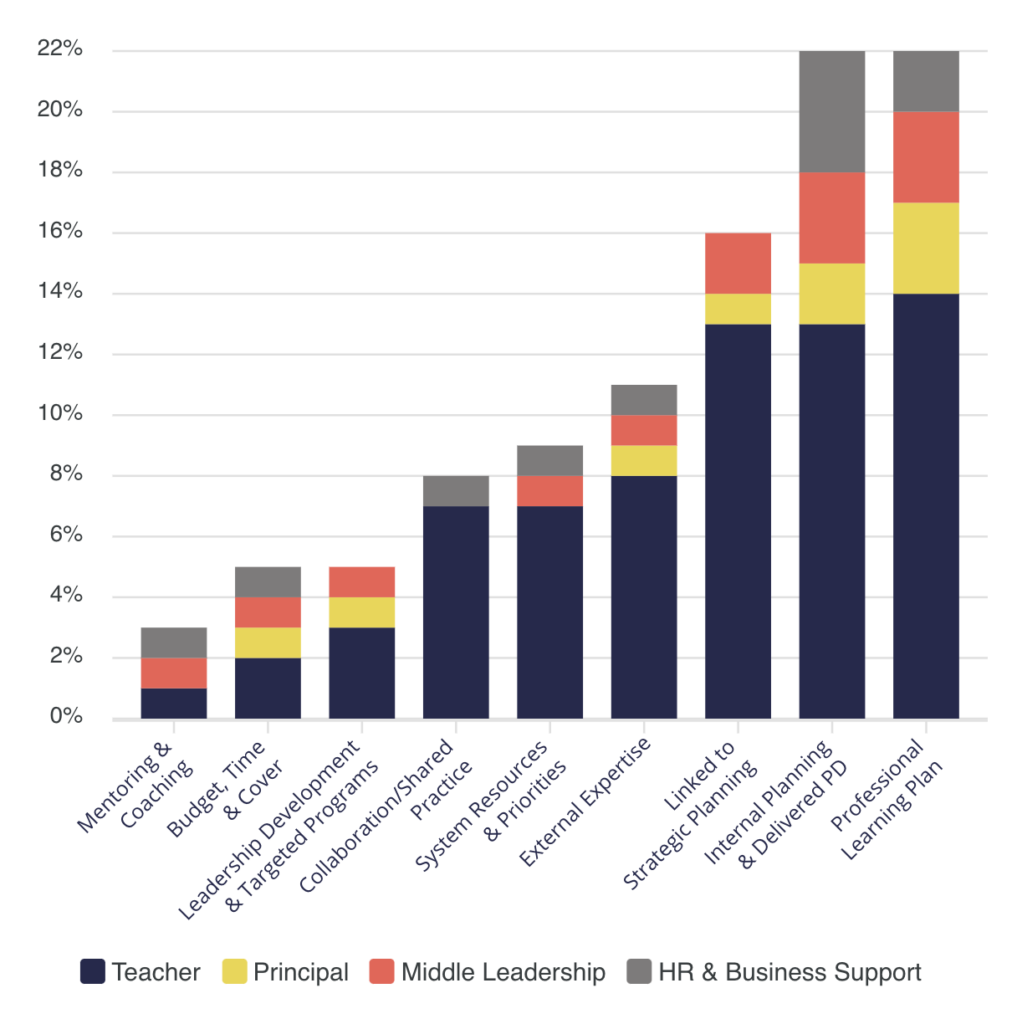

Addressing schools’ professional development priorities

As a follow-up to the previous questions, we asked respondents how their school intended to address its professional development priorities over the next three years.

Around 22% of responses made reference to a systematic approach to professional learning more broadly—this is assumed to reflect a planned and ongoing approach, distinct from specific individual Professional Development events or sessions (King 2016).

15% of responses focused on linking professional development to strategic initiatives. School strategic planning and school improvement is tied to funding and is typically intended as a 3–5–year roadmap to achieve a school’s vision, mission, and school improvement goals.

Approximately 30% of responses referred to professional development sessions, comprising ~20% references to internally-led and planned within the school and 10% references to externally run sessions. This supports the research that suggests the most effective PD is provided in-school.

Section six:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Continue to prioritise professional capability development as a key focus in their workforce strategies

2.

Stay across emergent research into the types of capability development (e.g., experiential, formal face to face training, online/hybrid learning, coaching/mentoring/shadowing etc.) that yield greatest impact on teacher learning and effectiveness

3.

Mature processes for determining which job families and role types in schools are most in need of professional development (for both Teacher and Non-Teacher roles) and which technical, professional, and interpersonal capabilities warrant highest priority allocation of time and budget in response to a constantly changing operating environment

4.

Continue to set success measures and monitor their return on investment in professional development over time, considering both impact on student outcomes and the experience of staff members as adult learners

Section seven:

The Impact of

COVID-19

Australian educators have navigated ‘unprecedented times’, ‘pivoting’ to the ‘new normal’ defined by the COVID-19 pandemic. There’s some light relief to be found poking fun at buzzwords, but the impact of COVID-19 on the education sector has been—and continues to be—acute, widespread, and sustained. As part of the 2021 State of the Sector survey, we asked educators specifically about professional development priorities and how the pandemic impacted these at an individual and school level. Explore their responses in this section.

Section seven:

Professional development changes as a result of COVID-19

When we asked participants how the COVID-19 pandemic had affected their school’s professional development priorities in a range of skill areas, almost all cited that Technological skills had increased in importance.

A considerable majority of respondents also reported that Managing own wellbeing, Pedagogy and lesson design, and Reflective and evaluative practice had increased in importance.

Principals were the cohort most likely to report increasing importance of professional development across these skill areas, followed by HR & Business Support staff and Teachers. Middle Leaders were the least likely to report an increase in professional development priority.

A small proportion (less than 10%) of respondents reported a decrease in priority.

How have your professional development priorities changed as a result of COVID-19?

Percentage of respondents by skill type.

Section seven:

How has COVID-19 led you to think differently about the school workforce?

Without doubt, COVID-19 has had a huge impact on many school workforces. Adapting to the constant disruption of the pandemic and ensuring education continues has emphasised the critical role teachers and school leaders play (AITSL, 2020).

The top themes in response to the impact of COVID on thinking about school workforces were Prioritising workforce resilience and wellbeing and Highlighting the importance of collaboration and teamwork, both within the workforce and the wider school community.

School workforce resilience and wellbeing has previously been overshadowed by student wellbeing. COVID-19 has rightfully refocused the lens to include school staff.

Educators have always risen to the occasion. During this time the calibre of their dedication, collaboration and teamwork has surfaced as evidenced in their responses.

Highlighting the importance of collaboration and teamwork

Emphasising the importance of connection with community

Acknowledging agility as an enabling factor in times of change

Highlighting the need to plan strategically for the future of the workforce

Prioritising workforce resilience and wellbeing

Section seven:

How has COVID-19 led you to think differently about the school workforce?

Section seven:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Examine where pre-pandemic School Improvement processes have contributed to changing to the way schooling is delivered, learning occurs, and working in a school is experienced. Consider which new processes and capabilities the school might need to harness the learnings of COVID-19. These will likely include a need for enhanced processes, capability, and capacity in:

- Service Delivery Model redesign (How will schooling be delivered into the future and how do we move from ideas to lasting change?)

- Organisational and Role redesign (How will schools be structured under our new models? Which jobs will exist in the future?)

- Workforce Strategy and Organisational Development (How will we ensure our future models are sustainable and continue to increase their positive impact over time?)

- Business Continuity and Scenario Planning (How will we remain ready for and robust to continued disruption in to the future?)

- Innovation design and implementation (How will we take a structured approach to piloting, testing, and costing new models? How will we roll them out if they’re successful?)

- Program and Project Management (How will we manage cost, progress, risk, and realisation of benefits as we move forward?)

- Change Management (How will we ensure that our communities and workforce enable and engage in this change?)

Section eight:

Looking to

the future

The disruption experienced by COVID-19 has added to the uncertainties and ambiguities around the future and what it holds for the education sector. Educators and education leaders are grappling with the opportunities and the risks they see ahead. Extending the horizon out three years, we sought educators’ perceptions of the factors that will have the greatest positive and greatest negative impact on the school workforce. In this section, learn more about their views of the future.

Section eight:

What can

sector leaders do?

1.

Engage school staff genuinely in the development of workforce strategies and provide visibility of intended investments in Leadership, Professional Learning, and Wellbeing

2.

Highlight specific actions intended to address workload challenges moving forward. Organisational improvement strategies used in other high complexity, human-centred community sectors include (but are not limited to):

- Service Delivery Model redesign (How will schooling be delivered in to the future and how do we move from ideas to lasting change?)

- Organisational redesign (How can we structure schools to allow staff to focus on the right type of work under the new models?)

- Role redesign (How can we design roles that reflect a realistic balance of tasks within these structures?)

- Process redesign (How can we organise activity at the school so that work is effectively prioritised and duplication of effort is eliminated?)

- Use of technology solutions (How can we digitise manual processes and use other technology to automate basic tasks that distract roles from their key focus?)

- Use of flexible work arrangements and alternative work patterns (How can we help staff to balance work and family life by creating opportunities outside the full-time norm?)

State of the Sector

Summing up: Where to now for school leaders and policymakers?

The 2021 State of the Sector report presents a detailed picture of the contemporary challenges and opportunities facing school workforces in the areas of sector sentiment, strategic priorities, supply, the HR function in schools, professional development, the impact of COVID-19, and future workforce possibilities.

In addressing these challenges and opportunities, the broad areas of focus and investment for school leaders and policymakers include:

- Taking informed and sustainable action on Workforce Resilience and Wellbeing

- Elevating the roles of Research, Data, and Impact Measurement in school workforce decision-making

- Redesigning Service Delivery Models—and the supporting organisations and roles—for the future delivery of schooling

- Prioritising systematic Workforce Strategy and Organisational Development for the greatest positive impact on students

- Undertaking Business Continuity and Scenario Planning to prepare for future disruption

- Ensuring action is underpinned by Program, Project, and Change Management for success

To discuss the findings in this report, or if you have questions, please contact us here or email [email protected].

The materials presented in this publication are provided by PeopleBench as an information source only. PeopleBench makes no statement, representation or warranty about the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of this publication, and any use of this publication is at the user’s own risk. PeopleBench disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including, without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages and costs anyone may incur as a result of reliance upon the information contained in this publication for any reason or as a result of the information being inaccurate, incomplete or unsuitable for any purpose.

State of the Sector

References

Ainley, J., & Carstens, R. (2018). Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 Conceptual Framework. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 187, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/799337c2-en

AITSL. (2020). Spotlight: What works in online/distance teaching and learning? https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/spotlight/what-works-in-online-distance-teaching-and-learning

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273.

Brady, J., & Wilson, E. (2021). Comparing sources of stress for state and private school teachers in England. Improving Schools, 13654802211024758. https://doi.org/10.1177/13654802211024758

Brown, C. (2014). NT bush schools facing teacher shortages next year. ABC Rural. https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2014-07-29/nt-bush-schools-face-teacher-shortage/5629140

Cameron , V. S., & Grootenboer, P. (2018 ). Human Resource Management in education: Recruitment and selection of teachers. International Journal of Management and Applied Science, 4(2), 89–94.

Cuervo, H., & Acquaro, D. (2018). The problem with staffing rural schools. Learning & Teaching. https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/the-problem-with-staffing-rural-schools

Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2017). Middle leaders matter: Reflections, recognition, and renaissance. School Leadership & Management, 37(3), 213–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2017.1323398

King, F. (2016). Teacher professional development to support teacher professional learning: Systemic factors from Irish case studies. Teacher Development, 20(4), 574–594. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/13664530.2016.1161661

Lobb, R. (2019). The Department of Education’s (WA) rural and remote training schools program. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 29(2), 99–100. https://journal.spera.asn.au/index.php/AIJRE/article/view/248

Phillips, L., & Cain, M. (2020). ’Exhausted beyond measure’: What teachers are saying about COVID-19 and the disruption to education. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/exhausted-beyond-measure-what-teachers-are-saying-about-covid-19-and-the-disruption-to-education-143601

Schleicher, A. (2018). What makes high-performing school systems different (World Class). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264300002-3-en

Sharplin, E.D. (2014). Reconceptualising out-of-field teaching: Experiences of rural teachers in Western Australia. Educational Research, 56(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.874160

Thomson, S., & Hillman, K. (2020). The Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018. Australian Report Volume 2: Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals. https://research.acer.edu.au/talis/